Williams has finally shown its hand for 2026, pulling the wraps off the FW48 in an online reveal that doubles as a statement of intent: this team wasn’t late to the party, it was still in the workshop tweaking the menu.

They were the only outfit not to log mileage at last week’s Barcelona running, a choice that raised eyebrows in the paddock given how abruptly the sport has turned the page with the new technical rules. James Vowles didn’t pretend it was comfortable. He called it “incredibly painful” at the time, but framed it as the consequence of pushing performance boundaries rather than missing a deadline. On Tuesday, the FW48’s unveiling gave that line some weight — and Vowles went further, telling media he “realistically” believes this is the best car Williams has produced under his leadership.

That’s a bold thing to say in public, and it reads as much like internal messaging as it does external bravado. Williams knows what it achieved in 2025 — fifth in the Constructors’ Championship, two podiums, and a sense that the team’s upward curve finally looked like more than a hopeful projection. The temptation now is to treat 2026 as a reset button that might scramble the order. Vowles’ subtext is different: Williams doesn’t want to be a feel-good surprise anymore; it wants to arrive as a serious, repeatable operation.

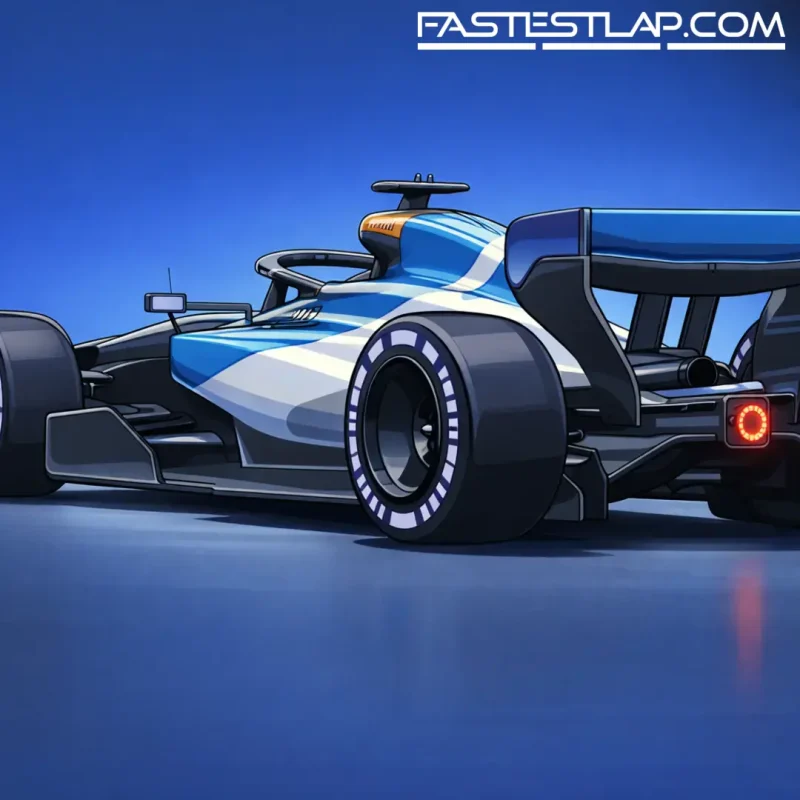

The FW48 itself is a visual marker of how different the new era is. With Formula 1 stepping away from the ground-effect philosophy that defined the previous generation, the 2026 cars are leaning harder on overbody airflow, and Williams’ first public images show a package designed around that shift. The other major ‘new normal’ is active aerodynamics — moveable front and rear wings — which instantly changes how teams think about lap-time and how drivers go about extracting it.

It’s not just a case of bolting on a clever system and letting it do the work. With active aero in play and the power unit balance shifting to a 50/50 split between electrical and internal combustion, the lap becomes a management exercise again — not in the old, clunky way of early hybrid-era lift-and-coast stereotypes, but in a more constant, decision-heavy rhythm. Drivers will be working the car’s modes and behaviour as much as they’re attacking corners, and the ones who can stay calm while multi-tasking at speed are going to make themselves extremely valuable.

That’s why Williams’ continuity matters. Carlos Sainz and Alex Albon remain in place, and Vowles was pointed about it: in his view, the “load on the driver goes up” in this regulation set, and experience plus what he called “high level intelligence” in the cockpit becomes a competitive tool, not a nice-to-have. In a season where everyone will be learning, having two drivers who can translate feel into usable direction — and do it quickly — is one of the cleaner advantages a midfield team can bank early.

The livery reveal was also used to underline Williams’ off-track momentum. Vowles described it as an “exceptional commercial winter” and highlighted Barclays coming on board as the team’s new official banking partner. That’s not window dressing. As the sport enters another development race and costs are funnelled into new areas, commercial strength is performance strength — especially for a team that’s trying to convert a recovery story into sustained competitiveness.

As for how the FW48 looks, it’s very Williams without leaning on nostalgia too hard: the familiar blue remains the anchor, there’s a clear white presence that nods to what the team ran in Austin last year, and red detailing still slices through it. Vowles seemed genuinely pleased to keep those identity cues intact, which matters when a team is trying to modernise without losing the thing people recognise.

Track reality, though, is still waiting. The FW48’s public debut comes ahead of a filming day, after which it will head to Bahrain for pre-season testing — Williams’ first proper chance to gather representative data with the car it’ll actually race. Bahrain’s three-day test begins on 11 February, and there’s a second outing later in the month, but nobody in the pitlane needs reminding that early pecking-order reads can be misleading under new rules. Still, as Vowles put it, even the first running has already looked “a little bit unpredictable” in terms of who’s where.

One quietly important note: Williams will run a Mercedes-AMG HPP 2026 1.6-litre V6. Mercedes has already put 500 laps on its package across the three days in Barcelona, and between Mercedes, McLaren and Alpine, the Brixworth-powered cars logged more mileage than any other manufacturer’s engine. That doesn’t guarantee anything come Melbourne, but reliability and early understanding are priceless when the whole grid is wrestling with new systems and new behaviours.

Vowles was careful not to oversell what’s coming. “We don’t expect to be fighting for the championship,” he said, while setting a clear internal target: make 2025 the baseline and keep moving forward from there. He also offered an unusually frank reminder of how steep the next step is. The jump from fifth to fourth, he argued, is “exponentially more difficult” than what Williams has already done — because you’re no longer chasing teams trying to survive, you’re chasing teams with infrastructure, momentum and the habit of finishing at the front.

That’s the real intrigue around Williams’ FW48 launch. It isn’t just another reveal in a busy pre-season calendar. It’s a team trying to prove it can make hard calls — even unpopular ones, like skipping Barcelona — and back them up with a car it genuinely believes in.

Now comes the part where belief meets timing sheets. The season begins with first practice for the Australian Grand Prix on 6 March. By then we’ll know whether Williams’ late reveal was a risk that bought performance, or simply a delay dressed up as ambition. In 2026’s new era, that distinction could be worth positions — and, for a team trying to muscle its way into the sport’s upper tier, it could be worth an entire season.